Young Honors Hoosier Lew Wallace’s Actions that Saved Washington 160 Years Ago

**Click here or above to watch Senator Young’s floor speech.**

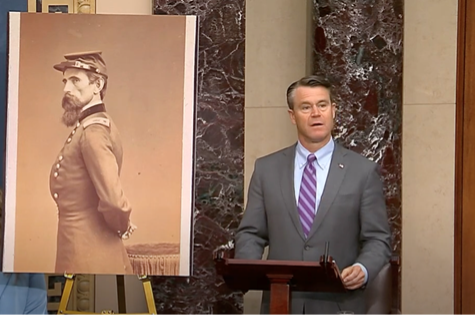

WASHINGTON – Today, U.S. Senator Todd Young (R-Ind.) spoke on the Senate floor about how Hoosier General Lew Wallace helped save Washington, D.C. on this date 160 years ago during the Battle of Monocacy.

On July 9, 1864, as Confederate troops were moving toward Washington, D.C., General Wallace gathered a few thousand Union soldiers to the Monocacy River in Maryland. There they battled over 15,000 Confederate troops en route to invade the nation’s capital. Ultimately, Wallace’s forces delayed the rebels long enough to prevent their attack of Washington.

“When it comes to words, Wallace will always be best known for Ben Hur. But the message he forwarded to Washington after the Battle of Monocacy, is timeless too,” said Young. “It should inspire us still, a reminder that rising to our duty, no matter the odds or even outcome, can change history: ‘I did as I promised. Held the bridge to the last.’”

To watch Senator Young’s floor speech, click here.

Senator Young’s full remarks, as prepared for delivery:

In 1864, after three years of civil war, many citizens of the North were ready for peace.

The Thirteenth Amendment had passed in this chamber, but failed to do so in the House.

And the fate of Abraham Lincoln’s presidency, and perhaps the continuation of the war, was on the ballot.

That spring Lincoln placed his hand on a Hoosier general’s shoulder and said:

“I believe it right to give you a chance….”

What he really meant was a second chance.

I rise to mark a day 160 years ago, when that second chance, and a refusal to flinch from duty, even in a forlorn hope, saved our nation’s capital.

And possibly much more than that.

Not long after his meeting with Lincoln, that same soldier was ushered into the office of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.

“What do you know of the Middle Department?” the Secretary asked.

“Nothing” his visitor replied.

“Nothing? The secretary repeated.

“I am from the West,” General Lew Wallace answered.

By the West, Wallace meant Crawfordsville, Indiana.

And that is exactly where he was when the year began, an officer whose career appeared to be at an end.

Two years before, the division under his command arrived late to the Union lines during the first day of fighting at Shiloh.

Wallace was scapegoated after one of the deadliest battles in the war at that point.

He was removed from his command in the Army of the Tennessee and placed on reserve.

Requests for reinstatement failed.

“I had cast my last throw. What next?” Wallace wondered.

The answer came from President Lincoln:

Wallace was to report to Washington and take command of the Eighth Army Corps and the Middle Department – even though he did not even know where it was headquartered.

The answer, Stanton told him, was Baltimore.

And that is where Wallace headed after buying a Rand McNally map of the U.S. for 15 cents.

In early July, Wallace sat at his desk studying that map closely.

He had just received word from the anxious president of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad that Confederate troops were advancing through the Shenandoah Valley.

The path from there to Washington was open. The city was poorly defended with Union soldiers away attacking Richmond at the time.

“Washington, seriously menaced, was incapable of self-defense – that much was clear,” he wrote years later.

Staring at the map, Wallace understood that the threat was real, and his responsibility was clear.

Without orders, he departed for Monocacy Junction, where the roads and railroad leading to Washington and Baltimore crossed a tributary of the Potomac.

Later he stood on a bluff looking down at the Monocacy River and the green pastures and golden wheat fields beyond it.

He could see the steeples of Frederick not far off and the Catoctin Mountains on the horizon.

The peaceful summer day was interrupted with the echo of distant gunfire.

Soon it was clear: Robert E. Lee had sent General Jubal Early north to take Washington.

He had crossed the Potomac and was on his way east, towards Monocacy Junction perhaps to Baltimore, more likely to Washington – 40 miles away.

Wallace had already moved with urgency:

He messaged Washington to recall troops and prepare for an attack.

He called in what brigades or parts of them he could to augment his own men…eventually rising a force of several thousands.

Then he spread them thinly along the eastern bank of the river, determined to block its bridge and fords long enough for reinforcements to arrive in the capital.

On the night of July 8th, the eve of battle, Wallace laid down and placed his head on a folded coat. But anxiety made sleep impossible.

Could he throw a hastily gathered and mostly green force in the way of a superior army, in an objective so hopeless?

Then he reflected on the consequences of not doing so:

The Navy Yard up in flames; the Capitol menaced, the library inside it looted; the treasury emptied; foreign heads of state rushing to recognize the Confederacy.

And then, most painfully, the image of Lincoln:

“cloaked and hooded stealing like a malefactor from the backdoor of the White House, just as some gray-garbed Confederate brigadier burst in the front door.”

The next morning, July 9th, when the Confederate army of over 15,000 arrived at Monocacy River, it was met with fierce resistance from the outnumbered Federals.

Rebel charges were repeatedly turned back until late in the afternoon, when Wallace, after heavy losses – nearly 1,300 dead and wounded – ordered his men to retreat towards Baltimore.

Early’s battered army paused for the night before it continued on to Washington.

When he reached its gates on the 11th, Union reinforcements were waiting. A skirmish at Fort Stevens followed and the rebels departed empty handed.

The Union stand cost the Confederates a day and with it their chance at Washington.

Monocacy is usually unmentioned among the list of consequential Civil War battles.

But today, on its 160th anniversary, we reflect on its importance.

Had Early’s men taken the capital, however briefly, the humiliation could have persuaded a war weary population to dismiss Lincoln.

What then would be the fate of the 13th amendment or the eventual terms of peace?

Because of Wallace’s resolve, and his men’s bravery, the questions went unanswered.

Lincoln was reelected.

The following January, the 13th Amendment, to forever end slavery, passed Congress.

The war was over by April and the Union preserved.

And General Lew Wallace, not unlike the hero of a novel he later wrote, was redeemed.

When it comes to words, Wallace will always be best known for Ben Hur.

But the message he forwarded to Washington after the Battle of Monocacy, is timeless too.

It should inspire us still, a reminder that rising to our duty, no matter the odds or even outcome, can change history:

“I did as I promised. Held the bridge to the last.”