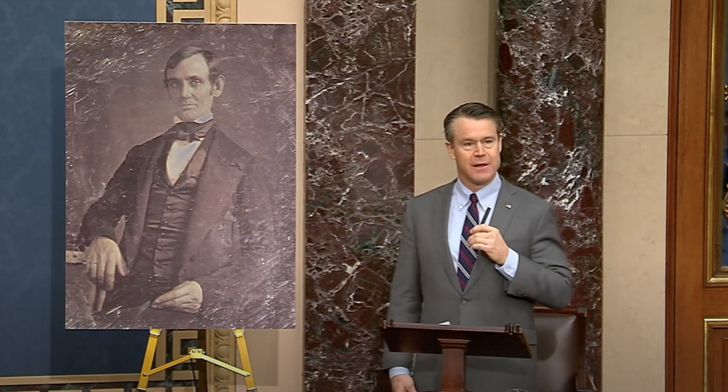

Young Commemorates Abraham Lincoln’s Birthday, Warns Of Political Division

**Click here or above to watch the full floor speech.**

WASHINGTON, D.C. — To commemorate the 215th anniversary of President Abraham Lincoln’s birth, Senator Todd Young (R-Ind.) spoke on the Senate floor about Lincoln’s 1842 “Temperance Address” and its lessons for today.

To watch the full floor speech, click here.

Senator Young’s full remarks are below:

As a Senator for Indiana, I can’t let February pass without offering a tribute to one of our state’s favorite sons…Abraham Lincoln.

As we approach his birthday, we celebrate how Lincoln’s story is perhaps the ultimate example of American opportunity.

Lincoln spent the formative days of his childhood in the Hoosier wilderness, and he ultimately rose from the humblest of circumstances, a log cabin, all the way up to the White House.

As President, he helped preserve our Union and end slavery, setting a course so that all Americans – regardless of race or circumstances – could follow his upwards path.

Lincoln challenged America to honor the promise in its Declaration of Independence that all men are created equal…

…and he reminds us still that if we fail to do so, government by consent of the governed cannot long endure.

I think all of us in here in the United States Senate today can attest that these are difficult times – we face all sorts of challenges, foreign and domestic – and therefore our politics are difficult. But I would argue, and I would do so here today, that the politics we’re facing today aren’t nearly as difficult as those that Abraham Lincoln faced.

During a week like this, where passions run high, we’ve had numerous debates behind closed doors and on this floor, we should keep perspective, and we should avoid dramatic comparisons and take dire predictions with a grain of salt.

But concern about the national discourse which informs our political system is indeed well-founded.

Dialogue between Americans, so essential to the maintenance of a democratic republic, has coarsened, it’s reached the point that at times it scarcely resembles conversation.

This form of estrangement leads to hurt feelings, separateness, civil dysfunction, and my fear, and what brings me down to this floor – it’s not just to honor a great man – I fear it portends to much worse divisions moving forward.

Abraham Lincoln knew this. He understood this dynamic.

Decades before the Civil War, he identified a remedy in an address that upset the residents of Springfield, Illinois.

Nineteenth century America was awash with passionate reform movements, much like today in the great American tradition. Many of their followers sought to cure societal ills with great zeal and commitment.

One example was the temperance movement. It’s sort of a dated term but the temperance movement was a campaign against drinking.

On February 22, 1842 – the 110th anniversary of George Washington’s birthday – Abraham Lincoln spoke to a gathering of reformers at Springfield’s Second Presbyterian Church as part of a temperance festival. Must have been a grand old time.

He was 33 years old. He was a member of Illinois’ House of Representatives, and as he later said, “an old line Whig” – a political party whose base, to borrow a modern term, included members of social reform movements.

But Lincoln did not use the occasion to curry favor with his base.

No. Instead, Abraham Lincoln offered advice still relevant to us today.

The invitation to speak came from Springfield’s chapter of the Washingtonian Temperance Society.

This organization was founded two years prior in Baltimore by six friends, all recovering alcoholics.

In a short period of time, the Washingtonians started a revolution in treating addiction.

The society’s numbers quickly swelled just a few years after its founding. Chapters spread across the country, into the frontier.

In the Washingtonians’ success, Lincoln recognized a particular means of building coalitions and addressing intractable problems.

And at its core was something especially relevant, I would argue, in our era of addition by subtraction:

As he put it, “persuasion, kind, unassuming persuasion…”

Previous efforts to curb alcoholism, as Lincoln recounted, were often self-righteous in their nature. Perhaps that characterization sounds familiar to some when we reflect on the current discourse. Self-righteous in their nature and impractical in their demands. Lest I sound quaint, that rings a bit true to me as we reflect on present-day Washington and the debates we sometimes have on this floor.

The Washingtonians’ approach and expectations differed, and that’s why they were successful.

They damned the drink, but not the drinker.

Their cure, such as it was, was based in compassion and understanding, not condemnation.

They saw a fellow citizen suffering from the disease as a friend in need of help, not a helpless sinner.

Lincoln contrasted the approach and effect of the Washingtonians with their predecessors, the older reformers.

The older reformers, Lincoln recalled, communicated “in the thundering tones of anathema and denunciation.”

Now we are all, no matter our political persuasion, familiar with those thundering tones.

The truth is we are all guilty of those thundering tones from time to time, and perhaps from time to time those thundering tones are appropriate and necessary and have a great deal impact when used sparingly.

We’re all guilty from time to time of forgetting that we are erring men and women.

But Lincoln suggested a gentler alternative:

“It is an old and a true maxim,” he reasoned, “that a ‘drop of honey catches more flies than a gallon of gall.’”

That’s how the Hoosier put it. It is that drop of honey, Lincoln continued, which draws men and women to our sides, convinces them we are indeed friends. Friends.

This from one of the most intelligent, successful, effective polemicists, debaters, litigators, and politicians in all of human history. He regarded his opponents as friends.

And this, in his words, is “the great highroad” to their reason… “when once gained, you will find but little trouble in convincing his judgment of the justice of your cause, if indeed that cause really be a just one.”

Some Lincolnian humility mixed in with age old wisdom.

Now across our politics and in our media, we seem so convinced sometimes of our justness, of our cause that it has become in vogue to cancel the other side and chase away those on our own who do not see them as enemies. Tribalism unleashed.

And where does the tribalistic impulse to cancel and ostracize lead us?

It’s an easy way to get booked on television these days. It’s guaranteed to increase the number social media followers you have. It might even rile up a rally or crowd from time to time.

But Abraham Lincoln, before the age of social media, predicted exactly where this would lead us:

Deem a fellow citizen a foe to be “be shunned and despised, and he will retreat within himself, close all the avenues to his head and his heart…”

It’s human nature and therefore unchanged and unchangeable.

“Such is man, and so must he be understood by those who would lead him, even to his own best interest.”

Abraham Lincoln believed that the American Revolution defied human history by proving men and women capable of governing themselves.

Our original birth of freedom led to the design of a republic in which citizens decide what is in their best interest.

But determining it often requires passionate, loud, angry debates, properly circumscribed by a social, moral, ethical framework that includes a balance with generous measures of trust and understanding.

An absence of this balance gives way to discord that makes us all weaker. Collectively weaker. Even individually weaker.

On the surface, Lincoln’s speech in 1842 was about a means of combating alcoholism and achieving reforms.

Look deeper though.

Its passages still today illustrate how we can continue to prove history wrong:

Remember the power of reason even in our most passionate arguments…

Find the empathy to form a bridge to our estranged countrymen…

And allow forbearance towards those among them we may disagree with.

Abraham Lincoln relied on these values throughout his career, even in America’s darkest hour.

They remain vital to our national harmony and common good.

So as we mark the occasion of Lincoln’s birthday in 2024, we should call on these values once again.